meeting

Sunday 17th September, 2023

As midday approached, with the sun fixed in the center of the sky, and with a high temperature, we crossed the Remanso bridge. Officially inaugurated in 1978 and 1300 meters long, physically uniting the Eastern Region of Paraguay with the Western Chaco, finally connecting the two countries. The name of the bridge comes from the place formerly known as “Remanso Castillo”, a place where several Spaniards, led by Captain Domingo Martínez de Irala, landed and settled.

Juan de Salazar de Espinosa first arrived in the area in 1537, 45 years after Columbus’s arrival on the island of “Guanahani,” possibly the present-day island of San Salvador, Bahamas. Salazar de Espinosa, who arrived in Asunción with Don Pedro de Mendoza, the first governor of the Río de la Plata, established the Fort “Our Lady of Asunción” which would be the foundation of the city. This was carried out in the territory of the guaraníes-caries, a town with which the Spanish conquerors formed an alliance. Irala, who was already in the region that same year, would be promoted to found the city upon the establishment of its council on September 16th, 1541.

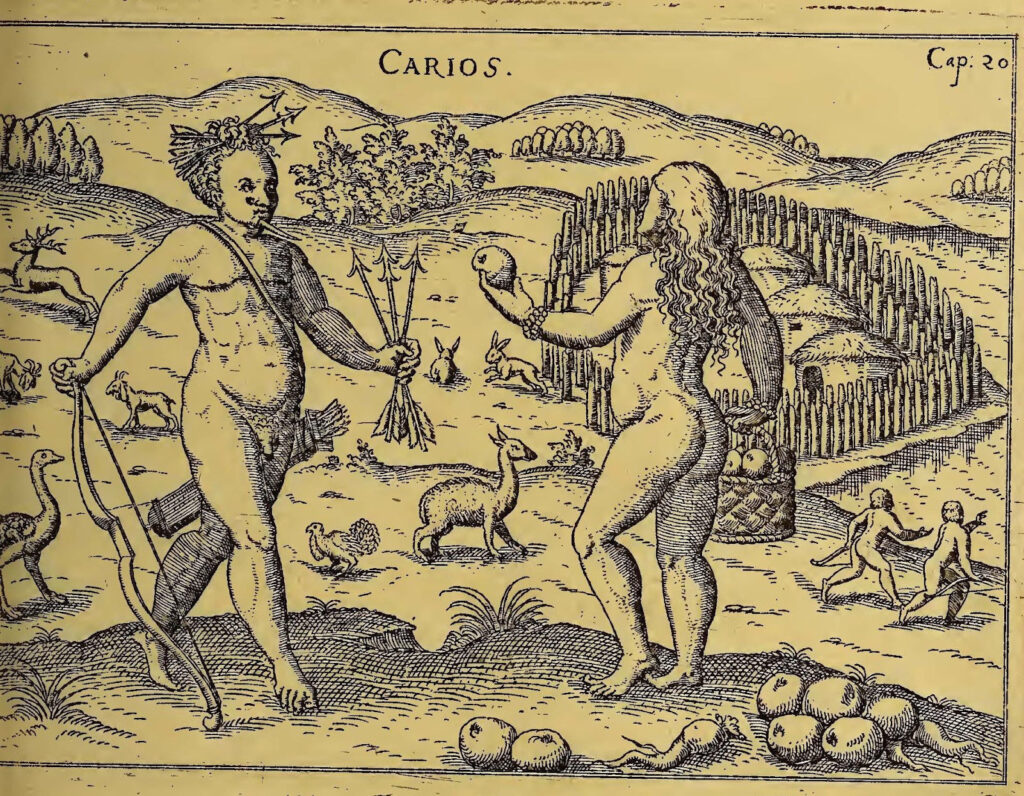

Asunción had its heyday in the second half of the XVI century, and then declined due to its geographical isolation and the neglect the Paraguayan province suffered at the hands of the metropolis. The founding of the fort that would give rise to the city of Asunción took place in the territory of the Carios, one of the Guarani tribes that inhabited the region “where they were farmers, and the harvest was done by the women. They also obtained other means of subsistence by gathering wild herbs and fruits. They hunted and fished in various ways, without depleting natural resources, allowing them to reproduce. They produced what was necessary for daily consumption, and the accumulation of products was completely unknown to them.”

guarani

The pre-Hispanic Guarani were organized into extended families, called teil or teýy, who lived in large communal houses called malocas. The teil constituted the basic kinship unit and was characterized by its high degree of political and economic autonomy. At a higher level of organization was the tekóa which could spatially coincide with a village or a group of villages. These tekóa could house up to a thousand people. However, since the Guarani practiced slash-and-burn agriculture, they were forced to move periodically to clear new plots where they could plant. Somehow the idea of founding a city, as the Spanish and Portuguese were doing, must have seemed ridiculous or terrifying.

Asunción embodies an enigma of the Río de la Plata Basin, its Mediterranean character, the same one that awaits the great city of Buenos Aires. Too crisscrossed by flows, too isolated in the middle of the continent. A hub of encounters or a closed space? Roa Bastos expresses that feeling of those raised and educated within Hispanic-European culture but living on its distant periphery, in one of those moments where the feeling of isolation overrides that of connection:

“Geographical isolation is compounded by linguistic isolation, by enclosure of its Mediterranean character, the double bilingual enclosure: coexistence, for four centuries now, of two languages, Spanish and Guarani —the language of conqueror and the language of the conquered— which serve in parallel, although complementarily, as communication tools to an entire community. This is a unique case in Latin America.”

Augusto Roa Bastos

Following the process of encounter and clash between the continent’s diverse ancient cultures and the newcomers from the Iberian Peninsula, we observe a capacity for movement and encounter, for violence and association, a dynamism completely veiled within the world-system where the metropolis is vibrant and the peripheries are dead ends, stagnant impasses of movement. But the capitalist and neoliberal world-system acts both as a material machine (in the plunder, mobilization, and accumulation of resources and in the establishment of infrastructure) and as an episteme, or mode of perception. The isolation of the peripheries is also a form of sentimental education, one that prevents them from seeing their own centrality.

Alexo Garcia

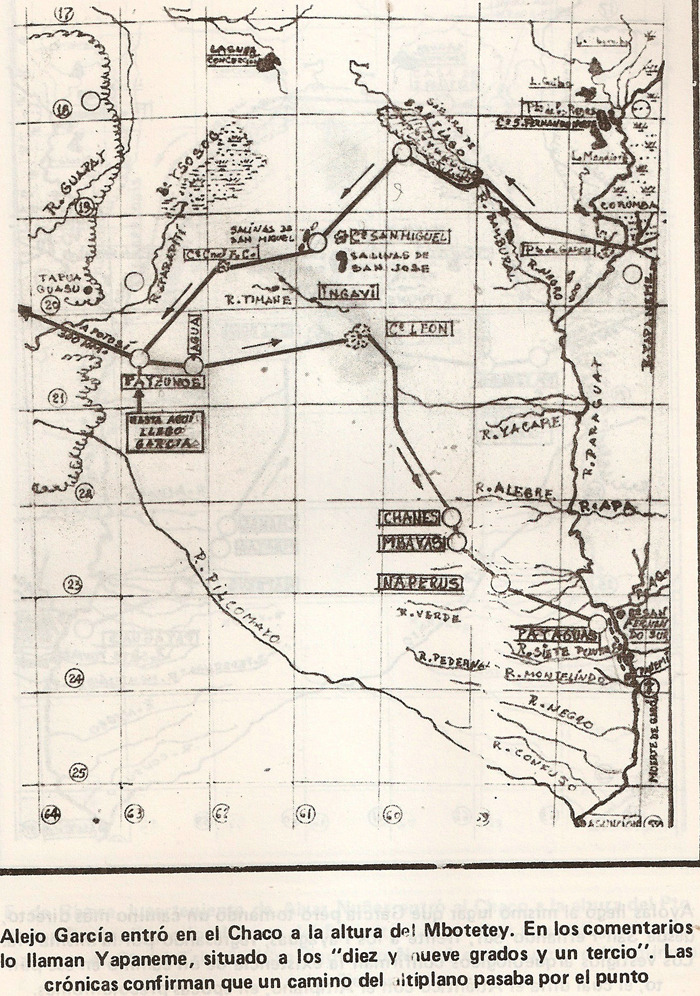

Alexo García was the first Spaniard to reach the territories of what is now Paraguay in 1524. He was also the first to make contact with the Inca Empire, preceding Francisco Pizarro. He was part of the Spanish expedition to the Río de la Plata under the command of Captain Juan Díaz de Solís, where they discovered Martín García Island. Located in the southeastern part of the Delta, unlike the neighboring sedimentary islands of the Paraná Delta, Martín García Island is a small outcrop of Precambrian rocks from the Brazilian Shield, dating back 1.8 billion years. It is surrounded by sediments carried by the Paraná, Uruguay, and Río de la Plata rivers.

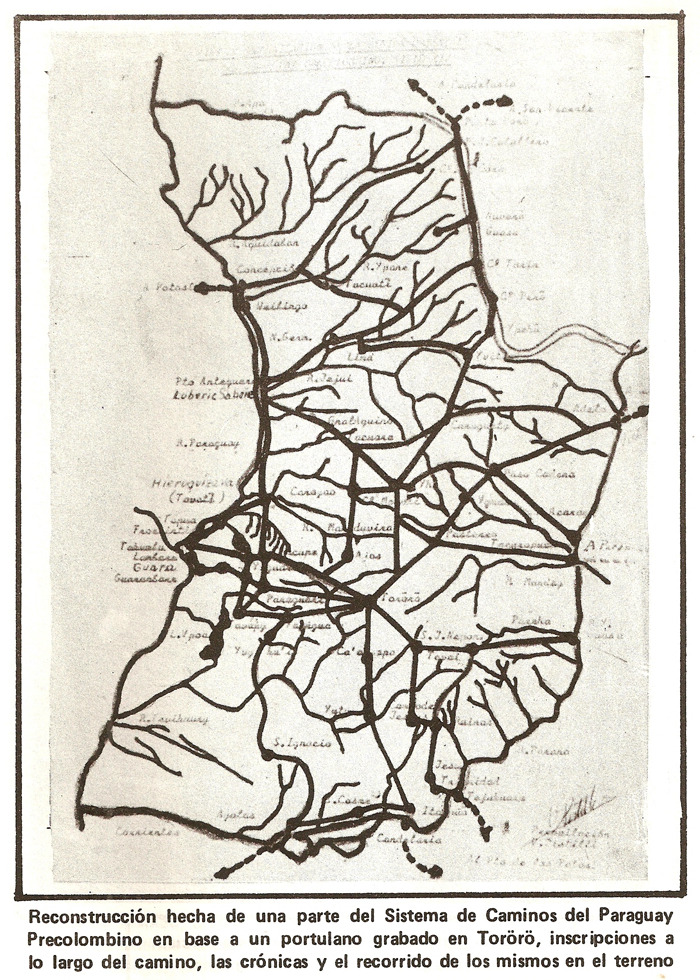

After being expelled from Martín García Island by the Portuguese around 1526, Alexo García landed in Santa Catarina, where he joined Guarani communities who adopted him as their leader. From there, he embarked on an extensive inland journey accompanied by some two thousand Guarani, crossing what would later become Paraguay for the first time by a European and making contact with the famous Peabirú road, which connected the Atlantic with the territory of Tawantinsuyo (the Inca Empire). He reached peripheral areas of the Inca Empire, where he obtained news and riches, but on his return, he was killed by rival indigenous groups, leaving his expedition as one of the first European attempts to reach the heart of South America.

encounters

An excerpt from “Guaraní and Spanish. First moments of the encounter in the lands of ancient Paraguay”, from Macarena Perusset:

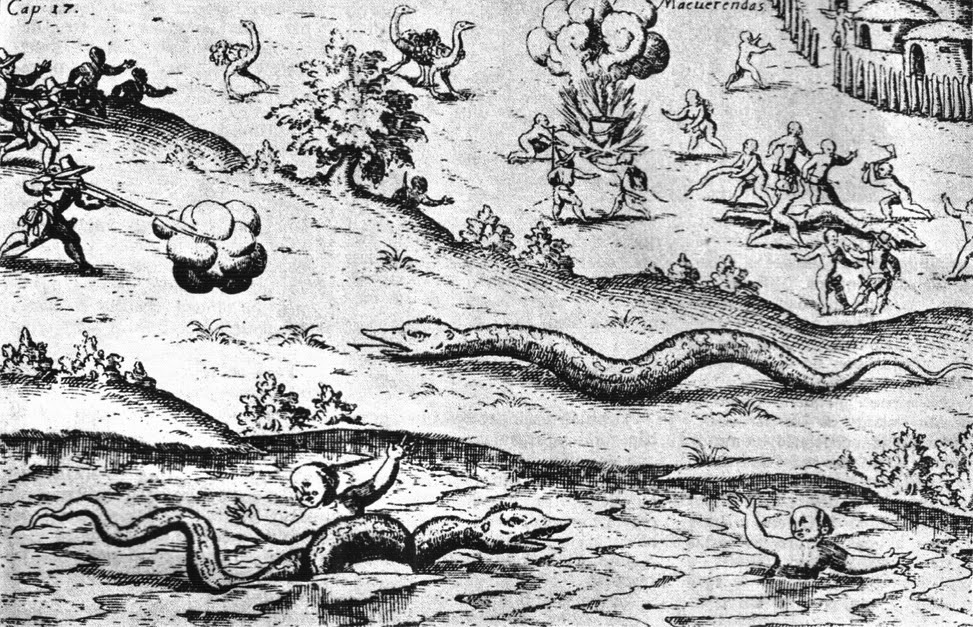

“The territory where the conquistadors settled coincided with the stronghold of the Carios, located between the Manduvirá River to the north and the Tebicuary River to the south. The areas around Lake Ypacaraí and the regions of Quiindy and Acahay stand out, as they were the sites of the first Spanish settlements. This was a true frontier zone, since to the northwest —in the Chaco region— lived various nomadic and warring ethnic groups. Among them were the Guaycurú, fierce hunter-warriors, described as ‘a people of war, day and night, for the sake of a nation, the bravest and most warlike of this frontier, which they call Guaycurú, a people so daring that they have not only destroyed many towns of the Guaraní nation…’.

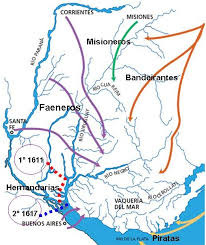

The Guaycurú people were divided into two branches: the Eyigua Yiqui, or southerners, and the Eyigua Yegi, or northerners, who often took advantage of the proximity of the Guarani settlements on the eastern bank of the Paraguay River to raid them, steal their crops, and devastate their communities. The Payaguá ethnic group also inhabited this region, characterized as ‘extremely cunning and treacherous, never missing an opportunity that would benefit them’. These territories not only saw contact between different socio-political groups but were also caught up in a context of dispute between the Spanish and Portuguese crowns over their colonial domains. To the eastern region, the core of colonial society, must be added the territory of Guairá, located east of the jurisdiction of Asunción, along the Paraná River. In this area, the Paulista bandeirantes gradually displaced both the indigenous and Spanish populations, as well as the missions that existed there, southward.”

“Although the initial encounters between the Spanish and the Carios were not encouraging for the conquistadors, they managed to prevail with firearms, securing the obedience and submission of some of the principal chiefs, who were embroiled in constant intertribal conflicts. In this context, the Spanish then forged an alliance with the remaining chiefs around Asunción, establishing a pact of mutual interests.

On the one hand, the Europeans needed the Guarani primarily for their crops. Likewise, the chiefs offered their young warriors as companions for their expeditions. Thus, the possibility of having a significant number of indigenous warriors, coupled with the availability of food, constituted the primary interest for the Spanish in formalizing this pact.

On the other hand, the Cario chieftains, who had been defeated in their encounters with the Christians, benefited from this forced alliance by requesting extermination expeditions against the Payagua indigenous people, who continually ravaged their villages and seized their women and crops. Likewise, it is likely that they turned to the Spanish to demand the extermination of other generations:

‘A cavalcade was organized against the Agaces, that is, a raid commanded by the treasurer general Venegas, who captured ten of their canoes. They were not the only enemies, because the Tapirus and Guaicurúes were also enemies, both for the sake of the Spaniards and for the preservation of the Carios…’”

Juan Francisco de Aguirre

mother of cities

Asunción was not only a crucial point in the conflictive and collaborative encounter between Guarani and Spanish cultures, but also a key geostrategic location for the construction of the Empire’s network of cities. Asunción was called, by the Spanish themselves, the Mother of Cities, as it became the center of the entire province. Expeditions departed from its ports to found other colonies. Examples of these included Buenos Aires, Corrientes, Santa Fe, Concepción del Bermejo (Argentina), Santa Cruz de la Sierra (Bolivia), and Santiago de Jerez and Ciudad Real (Brazil).

feral horses

Ten thousand years ago in Patagonia and what would later become the Pampas grasslands, the Hippidiones, a genus of horses, ceased to graze. Glyptodonts, giant ground sloths, and other large herbivorous and carnivorous animals also became extinct, driven out by climate change, the end of the ice ages, and hunting. But ancient humans, whose arrival date is still unclear, survived..

On May 11th 1580 a drove of 1,200 Andalusian horses (Equus Ferus Caballus), along with 7,000 cattle and an equal number of sheep, arrived overland from Asunción. This was a month before Juan de Garay anchored the San Cristóbal de la Buena Fortuna ship in the Riachuelo de los Navíos, a lower course that no longer exists today. The “saddle horses” along with the cattle were driven by sixteen men under the command of Alonso de Vera y Aragón, “whom they call Dog Face”. They skirted the waters along which would arrive Garay’s ships.

But as Mujica Laines indicates in The Founder, the animals of European origin were already there: “at the beginning of that same year of 1580, when he raised the royal standard calling the population of Buenos Aires, Garay promised that he would distribute among his companions the wild mares and horses that flood the pampa”: these had arrived with Pedro de Mendoza in 1536, and when the settlement of Nuestra Señora Santa María del Buen Aire was abandoned in 1541, between one and four dozen horses were lost, which “found a favorable habitat in the pampa grassland and reproduced amazingly, perhaps with a later contribution of animals that escaped from establishments in Santa Fe, Cuyo and Chile… Garay sighted numerous wild herds of mares near Cabo Corrientes, the present Mar del Plata; later the Salado basin was a place of abundant wild horses”.

They were no longer noble steeds nor tame milk cows. “The tame colt had become wild, and the calm, sleepy cow in the stable, a dangerous animal.” Before the century ended, the Pampas were riding with mastery and bartering horses for knives. In 1609, a document “…recognized that the Pampas indigenous peoples were already better horsemen than the Spaniards. Their people smeared their bodies with the fat of these animals and sacrificed them in the tombs, where they placed riding gear, a funerary custom that reveals the importance of horsemanship.”

Every indigenous person owned a small herd. The horse was the natural extension of their nomadic life. For their part, the first Spaniards had few animals, and they were used only for riding. The Spanish mentality, although busy with the movements required by the tasks of exploration and conquest, was oriented toward founding, toward settlement. Paradoxically, between life at sea and the construction of the city, the necessary movement across the immense territory was central yet alien to them. The city’s grid, a new arrangement on the continent, which was abstract and universal, nevertheless determined a situated, pedestrian, and repetitive, static habit. “The roads were almost impassable, full of dangers, and travelers had to face not only the lack of roads, but also swollen rivers, swampy terrain, and attacks by wild animals“, said Francisco Núñez de Pineda y Bascuñán in 1629.

The domesticated state of “beasts” is never stable, it depends on constant control. Exceptions of those that have definitively fallen into tameness are rare. Domestication is a gradual process involving generations of tamers and domesticated animals. Throughout the process, genetic and behavioral changes occur, and it can last for centuries. It requires the capture and raising of animals, followed by breeding and selection of specimens. A space analogous to a free territory is then constructed, but smaller and more controlled. Animals that temporarily escaped were called “orejanos” or “alzados” (rogue), but those animals that have returned to a wild state —that is, those that avoid humans and have become independent—were called wayward in Spain and then, cimarrones in America, But there, a runaway slave is also called a cimarrón.

In Cimarrón: notes on its first documentation and its probable origin in 1983, José Arrom quotes the dictionary of the Royal Academy: “…said of a slave or domestic animal that runs away to the countryside and becomes wild… Argentina. Said of bitter “mate” (traditional drink), that is, without sugar… Said of an indolent and unworkable sailor”, and then “in many provinces of America there are a great number of horses that have run wild or montarazes, whom we call cimarrones”.

Domingo F. Sarmiento, who, speaking of a cimarrón or child who escaped from their guardian, refers to the creation of the word in La Habana: “for the blacks and slaves who reached the top of inaccessible mountains and formed colonies, who were attacked with dogs trained for the purpose”. On the other hand “there is perfect synonymy within the montaraz and with cerril” and Corominas, the taking of the General and natural history of the Indies, by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, whose edition was published in Seville in 1535: “and the two meanings they list are ‘wild or cimarrón Indian’ and ‘wild or comarrón pigs’”.

Arrom then notes “further on I found another example of the use of the term cimarrón [in the General History…]”, which had gone unnoticed in Corominas. On this occasion the word appears in the following context: “[On this Spanish island] the fields are full of wild animals, as well as monteces (wild, originary to the mount) cows and pigs as well as many wild dogs that have gone to the mountains and are worse than wolves, and do more damage. And likewise, many domestic cats, which were brought from Castile for the dwelling houses have gone to the countryside, and those are countless the wild or cimarrones ones, which means in the language of this isle the same, fugitives”. The most widespread hypothesis states that “It probably derives from mountain peaks, where the runaway slaves fled”.

But Arrom finds another explanation: “Cimarrón logically should have meant a steep, rugged peak, difficult to access, but not the Indian or the Black person who fled to the mountains, nor the animals that went wild. It is equally illogical to think that the Indigenous people and the fugitive slaves, who knew the places where they sought refuge, occupied the peaks as a refuge, since both they and the smoke from their camps would be more easily seen by the monteros (mountain hunters) who would pursue them… All these reasons lead me to think that the proposed etymology is as fragile as it is unconvincing. On the other hand, there have been those who have postulated the possibility that the word is of Indo-American origin… if we pay attention to Oviedo’s testimony when, after having lived in Hispaniola for many years, he asserts that cimarrón ‘means, in the language of this island, fugitives’.

This is what some linguistic studies point to: it is not yet possible to say whether the word is Antillean or from some continental people, and if it is a term of Taíno origin, perhaps we should take a further step and venture the hypothesis of a possible etymology. Simarrón or cimarrón could be related to símara, a term that has been registered in Locono or Arahuaco with the meaning of ‘arrow’, and hence the compounds símarabo or símarahabo, ‘bow of arrow’. And when the root símara is modified by the termination -n, sign of the durative, which gives the lexeme the character of a continuous action, the símara could be translated as arrow released from the bow, escaped from the dominion of man or, as Oviedo says, ‘fugitive’.

And hence símaran is equivalent to ‘wild’, ‘jungle’ or ‘savage’. The two aspects, however, are symbols of a particular relationship between some individuals and some environment; summit/mountain/mountainous represent the spatial aspect, the situation, the act of escape. Símara is a technical object, a technical operation, a weapon. it expresses space and attack; it is an operation of causation and not of control, hence Arrom says “escape from the dominion of man”.

the first cows, the first horses, the first dogs

The first arrived with Pedro de Mendoza, founder of Buenos Aires, in 1536. As noted above, when they abandoned that settlement in 1541, between one and four dozen horses were lost, which then found a suitable habitat in the pampas grasslands and reproduced astonishingly, perhaps with the later addition of animals that escaped from settlements in Santa Fe, Cuyo, Chile, etc. In 1582, Juan de Garay sighted numerous wild herds of mares near Cabo Corrientes (present-day Mar del Plata), and later the Salado basin became home to abundant wild horses.

At some point, the indigenous people learned to use them, and by the end of the 16th century, the Pampas people near the second Buenos Aires were already expert horsemen, trading horses for knives and other goods and even eating them, as reported in 1599 by Governor Rodríguez Valdés y de la Banda. In 1607, indigenous prisoners were working in the Buenos Aires slaughterhouse, a job that required great equestrian skill. A document from 1609 acknowledged that the Pampas were already better horsemen than the Spanish.

While from Asunción the general Juan de Garay was coming down with the ships through the Paraná River, Captain Alonso de Vera y Aragón y Hoces did it by land, skirting those same waters.

On May 11th, Garay, at the head of the caravel San Cristóbal de la Buena Esperanza and other ships, anchored in the port on May 29, 1580, the day of the Holy Trinity. It was Alonso de Vera y Aragón y Hoces in 1587 who drove a significant number of approximately 4000 sheep and 8500 horses and cows to Paraguay in 1587. Thus Asunción became the center for the spread of livestock in the Río de la Plata basin.

We know that both horses and cattle arrived in our lands on the ships of the Spanish conquistadors. The native inhabitants of the region were unfamiliar with them, and the new settlers tried to keep them by building corrals as rudimentary as their makeshift dwellings. Horses were used for transportation and defense, while cattle were primarily for the provision of milk and dairy products, an invaluable staple food for the new inhabitants.

These animals, who had also discovered the fertile pampas, reigned supreme, reveling in this verdant paradise. Nearly 50 years passed before Juan de Garay refounded Buenos Aires in 1580. During that half-century cows and horses, without any trace of lineage, had multiplied endlessly. It is estimated that by the 18th century there were 40 million head of cattle. But they were no longer the noble steeds or gentle dairy cows they once were. Born and raised freely on the vast expanse of a bountiful plain, the tame colt had become chúcaro (wild), and the quiet, sleepy cow in the stable, a dangerous animal.

Juan de Matienzo, judge of the Audiencia of Charcas, in 1566 mentioned the need to open a door to the land, that is, to give an outlet to the Atlantic Ocean to all the territory that existed from Potosí southwards. He was only a few years old when, after fighting against the Araucanians, and with the purpose of founding Buenos Aires, the Adelantado, along with his lieutenant Juan de Garay, distinguished him as the main leader for having commanded the columns of settlers who would march overland from Asunción, Paraguay, with provisions, cattle, and a herd of Andalusian horses numbering no less than 1,200. This task was accomplished, it should be noted, a month before the founding, on May 11th, 1580, when he arrived at the port of Buenos Aires and, contrary to what some prominent historians have stated, he did so before Garay, who was coming down the Paraná River.

From Panama to Venezuela and from Venezuela to Brazil, the first cows arrived in what is now Argentina in 1556. They were a breed derived from the Turdetani stock and witnessed the second founding of the City of Buenos Aires in 1580. They quickly began to spread across the wide plains.

All this movement of horses, cattle, and dogs through the basin, and in the failed and abandoned settlements, generated animals that regained their wild nature, becoming feral, escaped, and almost untamed. Thus were born the large cattle ranches, a pre-modern productive and extractive phenomenon of gigantic scale. Over time, these practices became consolidated in a regional economic system, in which the capture of wild cattle was combined with raising them on ranches, especially in the province of Buenos Aires and the eastern pampas of Uruguay and southern Brazil.