origin(s)

We arrived in Mercedes – population 49,882 – a city of the province of Corrientes and the geometric center of the Mesopotamian region of the basin. This mesopotamian region includes the provinces of Entre Ríos, Corrientes, and Misiones.

The province of Corrientes has a diversified economy, centered on livestock, agribusiness, and forestry. Cattle ranching numbers over 4 million heads, and crops such as rice, tobacco, yerba mate, tea, cotton, and citrus fruits are grown, especially for the Brazilian market. It is the most forested province in the country, with pine and eucalyptus trees, and it has a wood processing industry, as well as processing of citrus fruits, rice, tobacco, yerba mate, and tea, in addition to yarn and textiles. It also houses part of the Yacyretá-Apipé Hydroelectric Complex, which contributes to electricity generation.

The origins of the city date back to the mid-18th century, in the context of defending the frontier against indigenous raids. In 1745, the Cabildo of Buenos Aires ordered the creation of the Luján Guard on the left bank of the river of the same name, which over time became a population center. That military outpost was established to protect the roads and ranches in the area, at a strategic point of passage to the interior.

Around the guard post families of soldiers, farmers, and merchants began to settle, forming a small village that grew with its own chapel and a bustling market. Over time, the settlement came to be known as Pago de los Arroyos de las Pulgas and then as Villa de Mercedes in honor of the Virgin of Mercedes. In 1865 it obtained the status of city, consolidating itself as an administrative and commercial center of the region, linked to the agricultural and livestock expansion and, later, to the arrival of the railroad.

estuaries

Very early in the morning we left for Asunción, Paraguay. It was impossible to pass through the Iberá Wetlands, which in Francisco de Amorrortu’s eyes are one of the great eco-thermomechanical machines of the great basin, geothermal energy depositary of “the formidable solar energy accumulated and continuously transferred as positive internal natural convective energy, from minor to major drainages and finally added to the great floods.”

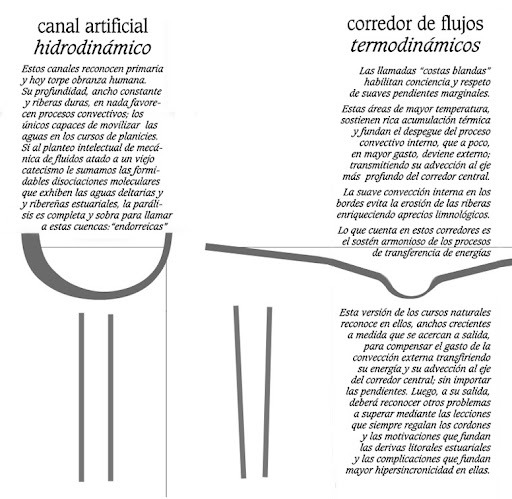

Francisco Javier de Amorrortu, in his writings on the site alestuariodelplata.com.ar presents a very critical view of what he calls “mechanical hydrology”, the “pipe hydraulics”. That is, the way in which engineering and water management often reduce river phenomena to simple balances of flows, pressures and canalization works.

In contrast, Amorrortu proposes to look at aquatic systems from the perspective of solar and convective energy as drivers of natural dynamics. According to him, water flows in estuaries, wetlands, and lower rivers are not sufficiently explained by “mechanical gradients” (slope, flow rate, gravity), but rather by thermoconvective processes where the sun heats the water, drives evaporation, generates vertical and lateral movements in the water column, and thus sustains ecological exchanges.

For Amorrortu, this vision is central because it shows that the wetland and estuary life depends on solar and convective energies that recycle nutrients, oxygenate the water, and sustain biodiversity. Criticism of mechanical hydrology points out that, by ignoring these processes, human interventions (canalization, dredging, rectification) destroy natural balances, since they treat water only as an inert fluid in a pipe, instead of as a living medium in permanent interaction with energy, climate and soils.

“Convective energies are the movements that occur in a fluid (such as air or water) when one part is heated more than another. The heat of the Sun is the primary source: by heating the surface of the water or soil unevenly, differences in temperature and density are generated, setting in motion internal currents. The warmer, lighter water tends to rise, while the cooler, heavier water sinks, creating a continuous circuit.”

“In bodies of water such as slow-moving rivers, lagoons, or estuaries, these currents can move large volumes without the need for gradient or mechanical flow. Force of convection is measured by the capacity to transport heat and matter: for example, in the atmosphere it is sufficient to sustain storm clouds that reach tens of kilometers in height, and in the oceans it drives vertical currents that fertilize entire fishing grounds. On a local scale, although it lacks the pressure of a flowing watercourse on a slope, convective energy can be more persistent and transformative, since it acts 24 hours a day on the entire body of water, with a power equivalent to millions of cubic meters, slowly but incessantly moved by the sun.“

Francisco de Amorrortu

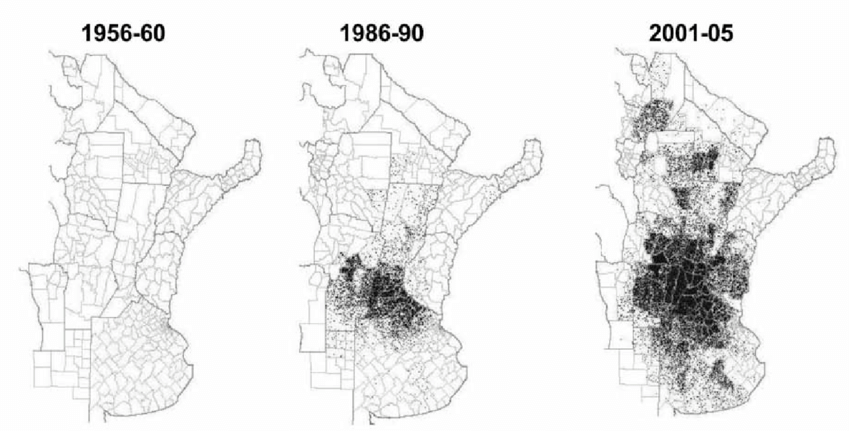

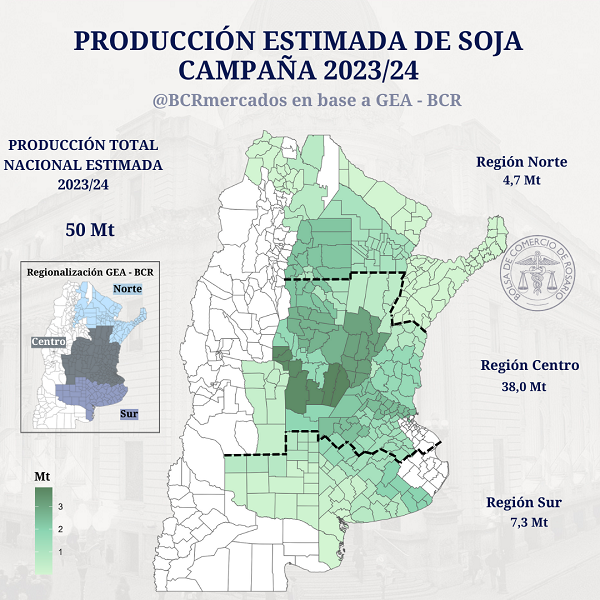

In recent decades, the Argentine agricultural model has undergone an unprecedented intensification, driven by the adoption of genetically modified seeds, no-till farming, and monoculture —particularly of soybeans— within a highly profitable technological package. This process, known as “Pampasization”, involved not only a dramatic increase in production —for example, from 12.5 million tons of soybeans in 1995 to nearly 39 million in 20051— but also a significant expansion of agriculture, as well as the expansion into areas outside the Pampas, with growth rates of the cultivated area of up to 220% in the NOA and 417% in the NEA between 1997/98 and 2004/05.

Walter Pengue characterizes this phenomenon as an extractive and dispossessing agricultural model where the encroachment on forests and grasslands translates into profound social and environmental displacement. He warned that this logic transforms agriculture into a system “without farmers,” dominated by large economic actors, such as planting pools and transnational corporations, while small and medium-sized producers are driven out2. It alleges that this model has generated an “ecological debt” because billions of dollars are required for fertilizers, which, however, are not enough to restore the structure of the deteriorated soil3.

This project is possible thanks to: