origin(s)

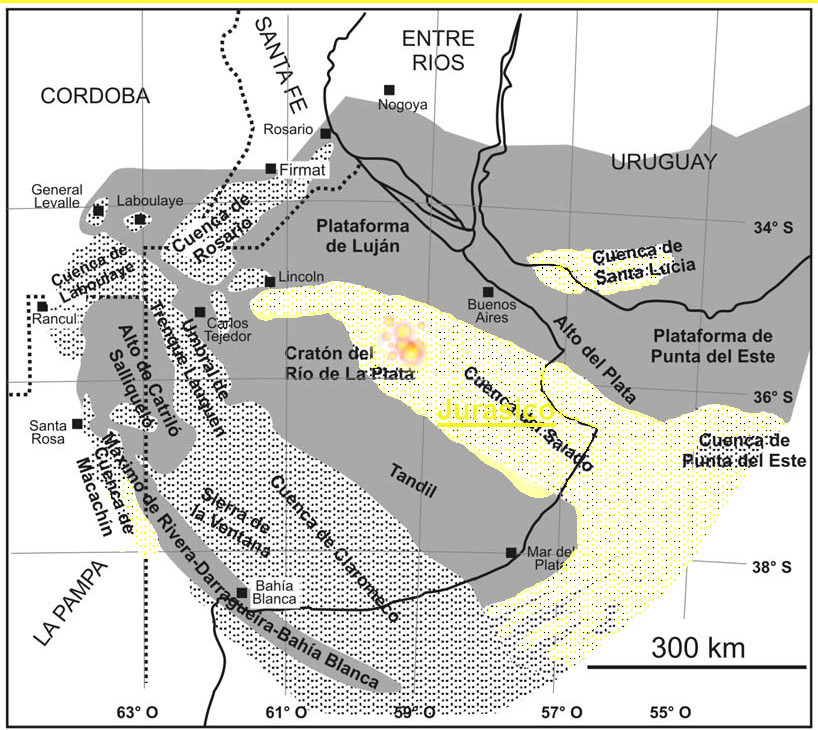

The Plata Basin originated as an intracratonic basin (a geological depression that forms inside a stable craton or continental shelf far from active tectonic plate boundaries) above the South American Platform, bounded by Precambrian cratons and shields, especially the Brazilian Shield to the north and east. Its main formation dates back to the Cretaceous and Tertiary periods, a product of tectonic subsidence and fluvial erosion, with sediment contributions from the Andes in the west.

Throughout the Quaternary the action of the Paraná, Paraguay, and Uruguay rivers deposited sands, silts, and clays that gave rise to extensive floodplains, wetlands and deltas shaping the current geography of the region. Furthermore, the Precambrian crystalline basement outcrops in high areas, while recent sediments form fertile soils that support agriculture and livestock, and facilitate navigation on the Plata waterway.

the sinking of a plate

In the case of the Plata Basin this means that the main depression where the Paraná, Paraguay, and Uruguay rivers accumulated was formed on the South American Platform, bounded to the east and north by the Brazilian Shield, a very ancient area of Precambrian crystalline rocks. That is, the basin developed in a tectonically stable territory but with the capacity to accumulate large volumes of sediment.

The Río de la Plata Basin was part of the southern landmass of the supercontinent Gondwana, although in the process of fragmentation. It gradually separated from Africa, Antarctica, Australia and India, giving rise to the nascent South Atlantic Ocean. The Plata Basin region was still relatively inland, with low relief and extensive incipient sedimentary basins. This region was part of the Craton of the La Plata River, one of the oldest units in South America, with crystalline rocks dating from between 2200 and 1700 million years .

a sea

The Paraná or Entrerriense Sea corresponds to a transgressive marine event which occurred mainly during the Upper Cretaceous, approximately between 100 and 66 million years ago, within the period when Gondwana was fragmenting and South America was beginning to separate from Africa.

Mar Entrerriense, Entre Ríos Sea, Paraná sea, Bravard Sea or the transgression of Entre Ríos is the name attributed to a vanished marine body that formed in the northern half of Southern Cone of South America during a marine transgression of Miocene.

The origin of the Plata Basin as an intracratonic basin is located in the Early Cretaceous (145-100 million years ago), when the first subsidences and accumulation of sediments occurred, while the Paraná Sea took place shortly afterwards, in the Upper Cretaceous, representing a marine transgression that brought marine sediments onto the already developing basin.

basement outcrops, stratification

Martín García Island is a rarity within the Río de la Plata estuary, as while most of the islands in the Delta are formed from Quaternary sediments carried by the Paraná and Uruguay rivers, the island directly exposes the crystalline basement of the Río de la Plata craton. This basement, composed of Precambrian gneisses, migmatites, and granites (between 1.8 and 2 billion years old), outcrops on the island as a small rocky enclave surrounded by more recent alluvial and estuarine deposits.

structure and singularity

The Martín García structure is recognized as part of a tectonic block that links the Uruguayan and Rio Grande do Sul shields in Brazil, acting as a geological window amidst the sediments that cover much of the region. For this reason, the island has great scientific value: it reveals the deep substrate upon which the Paraná-Plata basin rests and allows us to understand the structural continuity of the ancient crystalline terrains of southern South America.

waterfall rupture

They are formed by 275 waterfalls that plunge over a set of basalt layers of volcanic origin, whose differential erosion has generated the stepped shape of the terrain. There, on the border between Argentina and Brazil, unfolds one of nature’s most magnificent spectacles. The waters of the Iguazu River, a tributary west of the Paraná River, plunge up to 80 meters vertically, creating an incredible, almost kratosphanic display —the raw power of the planet’s external forces. We’re talking about an amphitheater of waterfalls 2,700 meters wide, where some 275 cascades plunge down, their waters roaring thunderously..

The original basalt flows occurred between 128 and 138 million years ago. How did this unique geological phenomenon occur? To understand this, we have to go back 140 million years to when the Atlantic Ocean was opening due to the separation of South America and Africa.

At that time, the entire Paraná River basin region was a vast red sand desert, not unlike the present-day Sahara. The breakup of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana caused enormous quantities of basaltic magma to flow from the depths, spilling onto the surface along extensive fissures. These flows of hot, black, ferromagnesian, liquid lava covered a vast area, burying the desert sands and creating one of the largest basaltic provinces on the planet. Today, these continental basaltic lavas form a broad plateau that extends over 1.2 million square kilometers across Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina.

layers of time – geology of temporality

Koselleck prominently used the extended metaphor of the geological layers of time throughout his work to separate and analytically dissect temporal developments and constellations:

“Sediments or layers of time” refers to geological formations that differ in age and depth, and that changed and distanced themselves from each other at different rates… By transferring this metaphor to human, political, or social history, as well as structural history, we can analytically separate the different temporal levels in which people move and events develop, and thus ask ourselves about the long-term preconditions of such events.

Towards a Cultural Geology: Merging Material and Conceptual History, Paul Kurek.

According to Koselleck, the advantage of thinking in temporal layers “lies in the ability to measure different speeds—accelerations or decelerations—and thereby reveal different modes of historical change that indicate great temporal complexity”. Consequently, one particular history may move faster than others, or even regress. For example, the French Revolution was a moment of acceleration in terms of political history. Later, in Nazi Germany, one could argue that technological history accelerated but social history regressed.

“Thus, the fact that historical time is not linear or homogeneous, but complex and multidimensional, explains the futility of all efforts to freeze history in order to delimit and define ruptures, discontinuities, time lapses, beginnings and endings,”

Koselleck is particularly interested in using geology to circumvent the dilemma between circularity and linearity, and through “Zeitschichten” (time strata), he records both “Einmailigkeit” (uniqueness) and “Wiederholenstrukturen” (repetition structures). The latter acknowledge the iterability that dominates human life without preventing the emergence of novelties. These are structures that control recurrences in different cultural spheres, such as the biological, legal, linguistic, and economic, to which Koselleck adds strata, which frame all singular events. This enables an analysis that considers movements, coincidences, and even shifts that explain how some phenomena follow a similar temporal course for a time and then deviate due to accelerations or decelerations, thus giving rise to new formations or recomposing, within the same temporal instance, what was once diverse. This scheme, which allows the identification of space-time interruptions, depends, strictly speaking, on a rejection of the vector of progress, which is projected on the basis of linearity and a homogeneous conception of time.