AMBA, departure

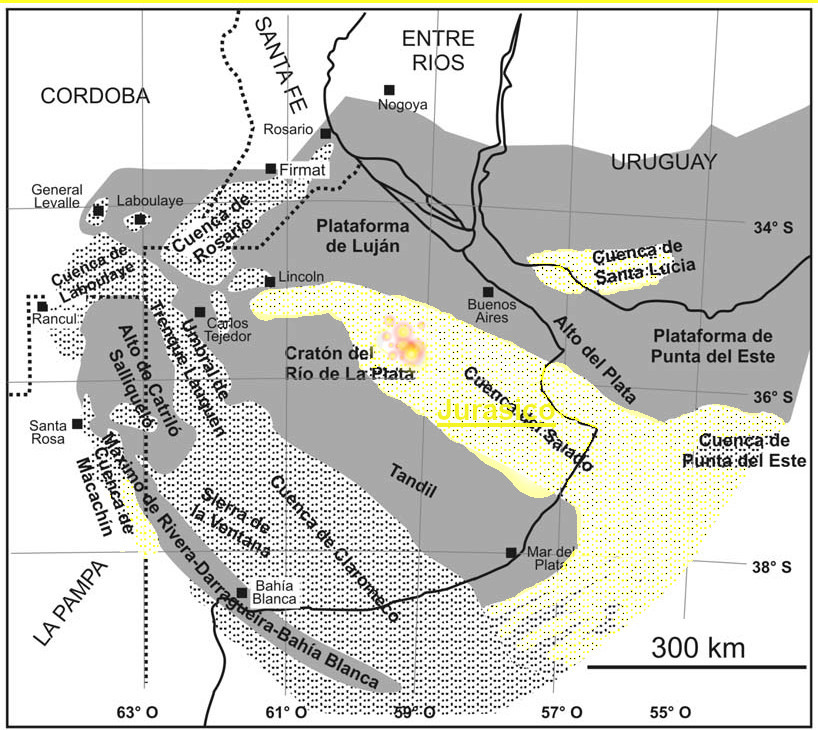

We departed on Friday, September 15th, from Buenos Aires, specifically from the Saavedra neighborhood in the northern part of the city. We crossed the AMBA (Greater Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area), both the most populated and most densely populated area in Argentina and southern South America, home to approximately 15 million people. Buenos Aires sits on the Río de la Plata, the estuary where the vast Río de la Plata Basin system flows into the Atlantic Ocean. The estuary is roughly triangular in shape, with a mouth 250 km wide and a length of 300 km.

Our final destination was Chiquitos, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, in the heart of the ancient Tupi-Guarani region. Santa Cruz de la Sierra was known as the Plains of Grigotá by the indigenous people Chanés, an ethnic group of Arawak origin that migrated from the Caribbean Sea 2500 years ago, occupying the plains of eastern Bolivia.

It took us a couple of hours to cross the AMBA – the country’s most important industrial and economic hub. The São Paulo Metropolitan Region (RMSP), the 18th largest metropolitan area in the world, has 23 million inhabitants. AMBA encompasses a conurbation made up of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and several nearby cities located in the Province of Buenos Aires.

Our first destination was Mercedes, in the province of Corrientes, a city of 33,000 inhabitants in the middle of a cattle-raising region.

This entire stage of the journey crossed the Argentine Mesopotamia region (provinces of Entre Ríos, Corrientes, and Misiones), whichis bordered by the Paraná, Uruguay, Iguazú, San Antonio, and Pepirí Guazú rivers. In the early afternoon, we arrived in Zárate to cross the Paraná de las Palmas and Paraná Guazú rivers, 80 km from Buenos Aires, via the Zárate-Brazo Largo railway complex, which features as prominent figures two cable-stayed bridges that are located about 30 km one from the other. The highways are spaced a distance apart, averaging 1700 meters in length, while the railway sections average 3000 meters. The view over the branches of the Paraná River is breathtaking.

The river forms a natural river transport corridor over 3400 km in length, extending through the Paraná and Paraguay rivers, and allowing continuous navigation between the ports of Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Overlaid on the water flow of the Río de la Plata system is a traffic of at least 102.6 million tons of various goods.

agro-industrial geopolitics, the great engine

In Argentina the total area sown with cereals and other agricultural crops was approximately 33.5 million hectares in 2020. It was projected to reach 34.8 million hectares by 2025, with a 4% increase compared to the previous cycle. This growth is partly explained by the expansion of corn planting, which could reach 7.8 million hectares, the second largest historical surface in the country.

In Brazil the total area sown for cereals, legumes and oilseeds was approximately 79.1 million hectares in 2020. A moderate increase was expected by 2025 with 80.5 million hectares. This represents an increase of 1.8%. This growth is due both to the expansion of cultivated areas and to improvements in productivity.

In Paraguay, the total planted area reached approximately 3.5 million hectares in 2020. A slight increase is projected for 2025 with 3.6 million hectares, a growth of 2.9% compared to the previous cycle, supported by improved yields and efficiency in production, especially of corn and soybeans.

Latin America is the region with the greatest inequality in land concentration in the world: 1% of rural landowners control 51% of agricultural land. While the region as a whole already has a high Gini coefficient of 0.79, South America maintains the highest concentration on the continent, with an index of 0.85. The expansion of the agricultural frontier, driven primarily by global demand for soy and beef, is the central factor in deepening poverty and inequality in access to land in South American countries, especially in regions identified as priority areas for agribusiness expansion and investment.

Estuary

“The fact that he called the river “Mar Dulce” (Freshwater Sea) shows his descriptive intention, and those who came later, after calling the estuary “the river of Solís” for a time, would eventually reveal their own motives, quite different from those of the discoverer, christening it, in the haste of the utility they attributed to it, the Río de la Plata (River of Silver).“

–Juan José Saer, The River Without Banks (Buenos Aires: Ediciones de la Flor, 1986).

The Río de la Plata is an estuary that marks the mouth of the vast Plata Basin, the second largest river in South America, formed by the Paraná, Paraguay, and Uruguay rivers. Its wide mouth, up to 220 km, connects the river basin with the Atlantic Ocean, articulating a transition between the fresh waters of the interior and the sea. Surrounded by the Humid pampas, its influence on the landscape, the economy, and urban settlements is decisive, especially in Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Internationally, it constitutes a strategic space for regional trade and transport, as it links the economies of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Bolivia with world markets.

flow rate and sedimentation

From the very shore of Buenos Aires, one can see the approach of the Paraná Delta, which in the region is called “Tigre” (Tiger) because of the native fauna the Spanish encountered upon their arrival. There, one can observe the dramatic nature of the city’s coastline and its profound geodynamic makeup, the slow sedimentation of the mud that the basin has been carrying from the foothills of the Andes.

“…on February 27th she announced that we were sailing up the Río de la Plata and that the next day we would anchor in Montevideo. On the 28th, at dusk, Graciela took me out for some fresh air. The river impressed me due to its ugliness and muddiness. It looks like it’s infested with sandbanks.”

-Mujica Lainez, Mysterious Buenos Aires

“And was it because this river of dreams and mud

that the prows came to found my homeland?

Tumbling about the painted little boats would go.

among the water hyacinths of the zaina current.”

-Jorge Luis Borges, Mythical Foundation of Buenos Aires.

“You can’t say the river changes one way in winter and another way in summer. It simply changes. That’s all. The islands, on the other hand, seem to change with every season… suddenly they’re there, suddenly they’re gone… The Paraná Delta, at its widest point, barely reaches 70 kilometers. But that’s just the beginning. Its magnitude extends far beyond that: 3,282 kilometers along the Paraná and 1,580 along the Uruguay. And even then, it’s not certain that it all ends there.”

-Haroldo Conti, Southeast.

In these literary fragments, we see how the river, the coast, and the islands of the Delta form a shifting, murky landscape, its edges indistinct; too flat and expansive. Water and land form a whole in constant exchange. The immensity of the Pampas continues into the Río de la Plata, without a fixed boundary of rocks, as in Montevideo, but rather as a shifting gradient from green to brown. This intermediate landscape between water and land, which was the perfect setting for smuggling, is the site of the slow and ever-changing encounter between the waters—which arrive from the interior of the continent and from the matter carried from the foothills of the Andes, along the Bermejo River, thousands of kilometers to the north, and along other rivers—and the Atlantic Ocean.

All this matter carried along by the thermo-mechanical work will slowly draw the basin closer to the sea; the Delta advances relentlessly and threatens the port city. Politics and pollution are illuminated by the light of this slow hydrological movement:

“All these riverbanks are riddled with interjurisdictional agreements. The discharge of 4,000,000 m³ of effluent daily, after a 12 km journey through cold outfalls, will create a massive bottleneck for the already catatonic and declining flows in the 80 km² area between the Emilio Mitre River and the urban riverbank, between Dock Sud and Tigre. The transition of the Mediterranean evolution of Buenos Aires is one step away from discovering the wake of a nauseating mudflat whose corpse we will mourn for 200 years. The average depth in that area does not exceed 80 centimeters.“

-Francisco Javier de Amorrortu.

the Delta of the basin

The Paraná River is the main river in Argentina and one of the largest in the world, both in terms of the size of its basin and its length and flow. It originates in Brazil and, after traveling more than 4,000 km, empties into the Río de la Plata in the province of Buenos Aires.

In its lower section, within Argentine territory, it has formed an extensive deltaic environment called the Paraná Delta, which is located mainly in Entre Ríos and Buenos Aires, and whose beginning is located approximately at the height of Rosario-Victoria.

From the border with Santa Fe, the Paraná River flows along the Buenos Aires coast and, at the height of San Pedro, it bifurcates into two main branches: the Paraná de las Palmas and the Paraná Guazú. Before entering the Delta area, the river has an average flow rate of about 20,000 m³/s, with peaks that can exceed 50,000 m³/s.

the sediments

“…between 100 and 160 million tons of sediment reach the estuary annually, and you learn that 72% of it comes from the Bermejo River, because the Pilcomayo River has been destroyed by hydraulic engineering projects. Today, the Pilcomayo loses 30 kilometers of its course per year. It’s losing course. The damage caused by these hydraulic engineering projects on the Pilcomayo is colossal. A disaster.

And the Bermejo River alone accounts for 72%. But hydraulic science, the National Water Institute, never inferred sediment journeys of 5,000 km. According to them, everything ends up here in the estuary. The Bermejo’s sediment reaches the estuary via the Paraná River basin. Uruguay has much less sediment, far less sediment, and energy. “

– Francisco de Amorrortu, interview conducted on 8/7/2023

We located the starting point of the sediment system in the areas surrounding Baritú National Park in Salta, bordering Bolivia. There, mountains that in some cases exceed 2,000 m in height deliver extraordinary sedimentary torrents during the copious summer rains, which the Bermejo River and its unique system of convective flows transport in a way never before fully appreciated.

In Amorrortu’s theory of hydrothermal forces and littoral drift, the actual and potential energy that mobilizes these unimaginable quantities of matter is not due to gravitational forces, but to thermal differences that generate flows, originating from solar energy accumulated in estuaries, wetlands, meanders, and shifting coastlines. The colossal engine of the basin couldn’t be mechanical. In other words, there’s no way to think about it mechanically in its entirety. Modern motorization seems to have no place, or perhaps only a marginal place, in the overall dynamics of a gigantic system that moves water, sediment, and living matter, on which not only human logistics and navigation depend, but also half of all agricultural and livestock production on the subcontinent.

“The Paraná de las Palmas River carries its waters at 1.3 knots, or 2.5 kilometers per hour. The Amazon River, which has half the gradient, instead of five centimeters per kilometer (over 2,100 kilometers), has a gradient of 2.8 centimeters per kilometer (over 6,700 kilometers), carrying its waters at four knots per hour, not 1.3. That’s three times the speed, or 7.5 kilometers per hour, with half the gradient.

How can that be? Well, every square centimeter of the wetlands surrounding the Amazon—in Manaus, for example— collects one kilowatt of energy per day. The energy collected by these wetlands exceeds 50% of all the energy consumed by the United States. The energy generated by the warm Gulf Stream, which isn’t the most important current on the planet—it’s the second largest—moves one hundred times more energy than all the energy consumed by humans on the planet.

-Francisco Amorrortu, interview conducted on July 8, 2023

“Archaeology —for all science is archaeology— is, to this day, irrefutable: until the arrival of the Spanish on the southern bank of the river, where Buenos Aires is located today, and in its immediate vicinity, there was no one. Whatever survived the last ice ages, happily awakening with the first warmth of the Holocene —human, animal, or plant— invariably avoided the flat, marshy areas near the river. Only the ambiguous, damp, and crawling fauna of the swamps teemed, along with the swarms of insects that darkened the air: ephemeral butterflies, horseflies, mosquitoes, and gnats.

The general term “vermin” (sabandija) that the Spanish used to describe that horde has survived to designate any harmful and despicable person, which indicates their perception of them, and they must have been excessively driven by their own delusion to confront them. The Indians, on the other hand, kept their distance. Those from the north—river nomads, hunters and fishermen of the Paraná and Uruguay rivers—almost never ventured beyond the delta, so as not to lose their footing or their sense of reality in those waters that, upon merging with the sea, widened and extended to infinity. Those from the south, despite the harsh climate, rarely crossed the northern limit of Patagonia, and even in 1869 they only traveled to the Atlantic coast out of necessity.“

-Juan José Saer, The River Without Banks (Buenos Aires: Ediciones de la Flor, 1986).

Atucha

The Zárate-Brazo Largo Railway Complex connects Zárate (Buenos Aires) with Brazo Largo (Entre Ríos) across the Paraná River, spanning two branches with bridges totaling approximately 4 km in length. It allows the passage of vehicles and trains, facilitates navigation and regional trade, and is key to the Mercosur infrastructure. Inaugurated in 1977, it was declared a National Historic Landmark. Before crossing into the Mesopotamian region, located between the Paraná and Uruguay rivers, and before tackling the great Zárate Bridge we made a detour towards the Atucha Nuclear Power Plant, in Zárate, Buenos Aires.

The Atucha Nuclear Power Plant is one of Argentina’s main nuclear facilities. It consists of Atucha I and Atucha II, both pressurized heavy water reactors (PHWRs), designed for electricity generation. Inaugurated in 1974, Atucha I produces around 362 MW, while Atucha II, operational since 2014, contributes approximately 745 MW. The plant is key to Argentina’s energy matrix and the country’s nuclear technological development; it produces 4% of the country’s electricity. It was the first operational nuclear power plant in South America, although the Angra’s I Nuclear Power Plant, in Brazil, construction began 4 years earlier.

It was promoted by the National Government through the National Atomic Energy Commission (CNEA), with technology supplied by the German company Siemens/KWU, based on pressurized heavy water reactors. Geopolitically and geoeconomically, the project is situated within the context of the Cold War, when Argentina sought to consolidate its technological and energetic sovereignty, reduce its dependence on foreign oil suppliers, and position itself as a regional actor capable of developing its own nuclear technology.